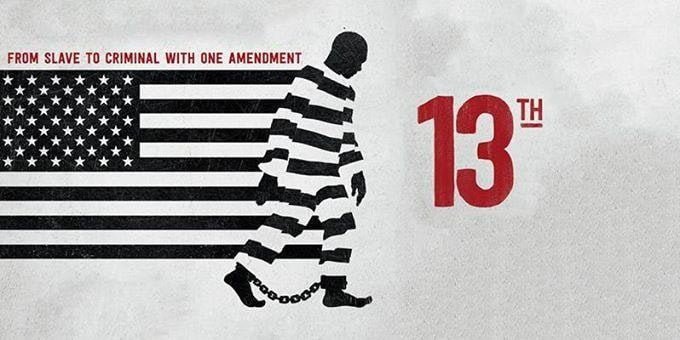

13th

The Thirteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution states that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

When the 13th amendment was ratified in 1865, its drafters left themselves a large and very exploitable loophole which they hid in its definition as a clause that is easily forgotten. This clause which changes slavery from being legal business model to an equally legal form of criminal punishment is what forms basis of the Netflix documentary “13th.”

“13th” premieres tonight at the New York Film Festival becoming the first ever documentary to open this festival since it began 54 years ago. Director Ava DuVernay takes an unflinchingly informed look at America’s system of incarceration based on extensive research and specifically how people of color are affected by it. At no other time was her analysis more aptly timed than today than now when we watch this movie feeling very irritated. As one watches the film, it builds up its arguments piece upon shattering piece leaving one shocked and outraged, making them feel disturbed before ending with a visual sense full of hope which draws us into becoming advocates for change.

“13th” opens with an alarming statement: One out of every four African-American males will be incarcerated at some point in their life. Our journey starts from there; with many familiar faces and sometimes unexpected ones filling up our screen frames with information. DuVernay interviews liberal scholars and activists such as Angela Davis, Henry Louis Gates Jr., and Van Jones but also provides screen time for conservatives like Newt Gingrich and Grover Norquist. Each interviewee appears against industrial imagery background supporting visually the prison-as-factory metaphor that begins in post-slavery era with 13th Amendment.

The economy of what used to be called Confederate States of America was decimated after the Civil War. Their economic mainstay, slaves, could no longer be required to provide them with free labor by shedding their blood, sweat and tears. That is unless they were criminals. The law states “Except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted” and that is the loophole. In an initial example of a ‘Southern strategy,’ many newly freed slaves were made to enter into free legal servitude through petty or trumped-up charges. The duly convicted part may have been questionable, but by no means did it need to be justifiably proven.

Each new version of cycle that DuVernay examines has another method of subservience-based terror waiting in the wings until one form falls out of fashion. Prominent among these are lynching, Jim Crow, Nixon’s presidential campaign, Reagan’s War on Drugs, Bill Clinton’s Three Strikes and mandatory sentencing laws and our current cash for prisoners model leading to millions for private bail and incarceration firms.

This was a big point of discussion in “13th” wherein there is an onscreen graphic with figures that keep increasing as years go by to show the number of people behind bars. From the 1940s, the curve of the graph representing prisoners counts starts ascending slowly but steeply. A meteoric rise began during the Civil Rights movement and continued into the current day.

As this statistic rises, so does the level of decimation of families of color. The stronger the protest for rights, the harder it fights back against it through means of incarceration. Profit becomes one major by-product of this cycle, with an organization called ALEC providing a scary influence for building laws that make its corporate members richer.

At various points “13th”, however, has jarring cuts to a black screen filled by only one word CRIMINAL in white that is centered on screen fills up completely with this word. All too often people only see them as people colored and not whoever they are; therefore at some point DuVernay takes us back to D.W Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation”, which helps trace how African-Americans became associated with being superhuman bad guys who were frightening Whites into believing that Black ones were demonic beasts lacking human feelings or desires.

The dehumanization process allowed those biased laws and ideas to be accepted without any backlash whatsoever. We have seen more jail terms given out for crack as opposed to cocaine possession plus innocent individuals accepting plea deals since they are scared stiff about going before jury panels. Furthermore, we also discover that a significant percentage cannot be released from jails because they lack money required for bails’. Also, if convicted as felon, your ability to vote for changes including having yourself prejudged unfairly has been taken away from you like every other American citizen must lose their basic right.

“13th” covers many miles as it gets us closer to today’s Black Lives Matter movement and then moves all the way into endless videos of African Americans being gunned down by police or “standing their grounds” as well. On her journey to this point, DuVernay doesn’t let either political party off the hook, nor does she ignore the fact that many people of color bought into the “law and order” philosophies that led to the current situation.

We see Hillary Clinton talking about “super-predators” and Donald Trump’s full-page ad advocating the death penalty for Central Park Five (who, as a reminder were exonerated). We also see people like African-American congressman Charlie Rangel who originally was on board with President Clinton’s tough on crime laws.

“13th” has already proved its thesis through various means before reaching the montage of Philando Castile, Tamir Rice and Eric Garner deaths among others (not to mention a large graphic that covers the entire screen with the names of African-American shot unlawfully by police). In other words, this scene is another heartbreaking moment in “13th”, which follows an onscreen conversation about whether or not black bodies should be destroyed continuously on cable news. Duvanray chooses to depict these images herself, stating that she respects their families’ permission for her to show them. She didn’t have to, but she did.

“13th” seeking answers between its lines as pointed out above asked if African Americans were ever truly free in America. We are freer than our ancestors who were once enslaved though it may seem so easier for people in this generation but the question still lingers on the possibility of being entirely free like our White countrymen. If not, isn’t there a chance that when all things will be equal? The final point derived from “13th” is that changes should not come from politicians but rather from Americans hearts.

Capping off such a heavy film on such a light note is DuVernay’s inclusion of scenes showing children and adults of color enjoying themselves in various activities. According to her discussion with NYFF director Kent Jones during Q&A sessions, DuVernay wants us reminded that “…Black trauma is not our entire lives. There is also Black joy.” Henceforth, ’13th’’ becomes something one must watch because it carries an inspiring message underscored by this well-informed documentary work.

Watch 13th For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)