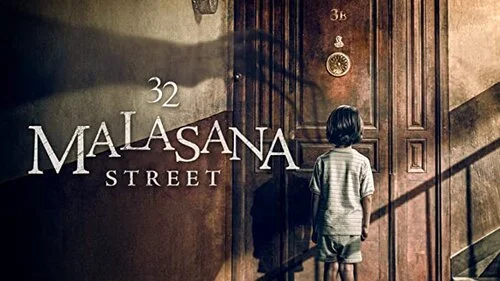

32 Malasaña Street

32 Malasaña Street has a better technique of cutting sharply than it does scaring you, and yet this would have seemed to be an essential editing skill for the horror genre. However, director Albert Pintó backs up his family in a haunted apartment tale with a lot of predictability but occasionally jerks the story into life by dropping WHOOSH! a dress onto the floor or BANG! someone buffing a hood ornament. At first, the movie avoids clichés and later on it is just offensive in its simplicity.

It is set in 1976 Madrid and follows the story of a poor family who moves from their village to the city. This choice of moving causes several controversies because they are poor. But Olmedos want to try making things work out without knowing about anything sinister that went down in that flat before (some of which we witness in mildly disturbing opening prologue involving two boys and one unresponsive elderly woman).

Meanwhile, as Manolo (Iván Marcos) and Candela (Bea Segura) seek for some way to make money after this relocation, their oldest daughter Amparo (Begoña Vargas) watches over her two brothers lonely Pepe (Sergio Castellanos) and anxious Rafi (Iván Renedo). Rafi is a five-year-old boy whose eyes are always wide open; he sleeps in Grandpa Fermín’s bedroom, starts seeing eerie sights at night within their apartment. It claims inspiration from real events but looks more like “inspired by James Wan’s ‘The Conjuring.’”

There is nothing particularly new here; indeed it’s one of those movies where if you were to give away its clichés you would spoil most of its major plot twists. This becomes acute when we come across central scary scenes trying to put us into shoes of frightened relatives who though dark rooms in an apartment meticulously while a camera’s point of view matches their fixed gaze from one side to the other and back.

This is the type of uneasiness that “32 Malasaña Street” initially succeeds in, but later we increasingly get its pattern of jolts. Meanwhile, the story does not move beyond informing everybody that this apartment is indeed cursed, and thus its predictability has become a breeding ground for clichéd episodes as well.

The most interesting part comes in halfway through and just last for some scenes. After every member becomes aware of such things as closing doors but their own house, they are homeless (like when the family in Wan’s “Insidious,” just moved to another big house). The Olmedos have no money; they need to go back to work.

In such brief moments as these, it alludes to something much scarier about being unable to provide for loved ones even if it uses your concern for Olmedos very effectively. Also, these flashes show better acting compared with remaining hands trembling and nails biting while trying too hard at creating an atmosphere during Pinto’s slow grinding non-entities.

“32 Malasaña Street” quickly abandons this financial aspect of the plot line only to deteriorate further as a movie.

What the movie needs in its third and final act is some off the wall, unpredictable scenes that will make it bulkier; thus, it presents offensive depictions of physically challenged or transgender people whose identities have been othered and positioned as either magical or monstrous. These are the only parts of the story that stand out, and their presence justifies how much of a cliché this film has become. That these elements are still being used in current horror stories goes to show how far behind they actually are.

Watch 32 Malasaña Street For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)