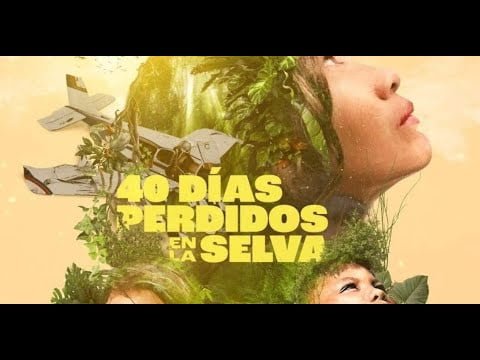

40 días perdidos en la Selva

The Children of the Amazon. 40 Days Lost in the Jungle is Colombian journalist Daniel Coronell’s first novel, though his credentials alone are enough to warrant anyone’s attention: news director at multiple networks; recipient of such accolades as Emmys, Peabodys and Simón Bolívar prizes; quite possibly Colombia’s most widely read columnist, admired as much as he is feared. His intelligent investigative journalism incisive, meticulous, razor-sharp but with a mildly ironic humour has unearthed many of that country’s biggest political scandals.

This bravery in speaking truth to power has made him something of a hero among his readership, who cherish him as a national treasure in the absence of anything resembling an independent judiciary. But such courage and renown come at a price in Latin America. Having been bombarded with death threats and dark warnings an occupational hazard for someone like him.

Coronell was forced into exile in the mid-Noughties along with his family, who settled in Miami. Thankfully his desire to expose the misdeeds of the powerful and his indomitable spirit are showing no signs of letting up: he currently serves as president of Univisión News and works for W Radio Colombia while continuing to write regularly for Los Danieles.com, an online portal where he enjoys a warm relationship with his adoring public.

Given all this it is hardly surprising that any book by Daniel Coronell not just another collection of op-ed columns like Recordar es morir (2016), which was hailed as an “unsparing colonoscopy” of Colombian politics should be seen as nothing less than an event. But Los niños del Amazonas is not your typical ‘Coronell fare’: drug money; unsavoury characters; Benthamite justice systems only technically more crooked than their alternatives; lethal violence; these are all present here, but they play second fiddle to other things.

Instead the book deals with what was, in 2023 at least, a well-known story: that of four huitoto indigenous children whose plane crashed in the Amazon and who managed to survive on seeds and fruit for 40 days until they were found. It could have been just another tale of human suffering and endurance like, say, the 1972 Andes-plane crash, cinematically spectacularised in J.A. Bayona’s Society of the Snow (2023), or a proud member of the long fictional lineage that stretches from Robinson Crusoe (1719) through The Jungle Book (1894) to The Lord of the Flies (1954) were it not for certain distinguishing features such as, among others, the fortuitous intervention of a shamanic figurehead and his yagé-induced visions.

Most of Coronell’s procedural columns follow a descent into hell, but in this book it is more like an upward journey. For him trauma and suffering are merely preludes to heroism and salvation; vices and virtues of the entire nation as much afflicted by racism, violence, and inequality as it is endowed with generosity and courage. So there is no wonder he wrote this novel during a personal crisis that was also familial in nature. “A lot of these pages were written through tears,” he says in his acknowledgments, because at the time he received “the most terrible news” along with “some hopeful ones” (217). He did not sleep while writing it; feverishly composed it over several nights as “a way to save myself,” as he said in an interview recently published.

That this captivating story of personal and national redemption should be infused with professional skill comes as no surprise from someone like Coronell. He has made sure to gather all available evidence up until now and put them together into what can only be described as a lively text though still not quite reaching the level set by older Colombian chronicle masters whom he always admired such as Germán Castro Caycedo.

The Amazonian context is adequately set up; huitoto people’s customs, beliefs, continuing historical-cultural struggles are given their due coverage; the four children 13-year-old Lesly, her nine-year old sister Soleiny, Tien Noriel aged four years plus baby girl Cristin Nerimán, Magdalena their mother and Miller their stepfather prone to domestic violence are introduced; we come to understand why on May 1st 2023 Magdalena decided together with her offspring take that fateful flight final destination being Bogotá where she had gone hoping for better life since Miller stayed behind in capital city while risking everything for this new beginning.

Coronell also dissects meticulously technical details concerning Cessna’s failure which led emergency landing among canopy trees in Amazon, causing instant death its adult passengers but leaving behind children who had now to survive themselves within dangerous forest. Then he tells us about slow moving diverse search party (military forces specialized in jungle warfare along with indigenous trackers armed with dogs), their structure set up, internal wrangling that at first seem to help it make progress and later on when false alarms become recurrent leading demoralization as kids turn out be more slippery than was earlier thought.

He describes involvement cross culturally sensitive manner of huitoto elder Don Rubio who takes control over these desperate rescuers by going traditional route taking yage psychotropic drink better known as ayahuasca thereby locating lost kids thus bringing an end what had been called “trying spot flea huge rug” mission (108).

There is even brief epilogue mentioning subsequent recovery children; stepfather Miller being imprisoned accused sexually abusing them; disappearance one beloved trained Malinois dogs named Wilson. Throughout book various reports are quoted from, texts referred to, interviews conducted all these were possible because author had access wide array sources. In strictly informative terms therefore Los niños del Amazonas provides definitive account what actually took place based on facts alone.

And still the book, if you pay attention when reading it, gives much more than what the above quick summary says. As a matter of fact, what happens to the children represents all Colombian problems which are related through different ways. It is true that this dark history is not deeply covered by Coronell but you wish he had because it could have been a springboard for further discussion.

Nevertheless, some might argue that those questions deserved closer examination but that would only make more difficult an otherwise plain and meticulous account of events. However, any way these matters may be explored are found throughout every page of Los niños del Amazonas; they are its deep social-historical foundation on which events happen.

The first thing that comes up is about the giant territory called Amazonia in Colombia according to Coronell: even though it occupies 42% of the land and only has 2% population density, this wide green space has been both very attractive and totally incomprehensible for people who lived there or heard stories about them from afar.

The jungle is shown as an enigmatic place where nobody wants to go but many have tried entering then never come back again such as in La Vorágine (1924) by José Eustacio Rivera or El abrazo de la serpiente (2015) directed by Ciro Guerra; during those times people used rubber while now it’s coca fields worldwide, international traffic with animals and deforestation being a matter of global concern at present. These groups suffered culture destruction due capitalism racism sexism colonialism etcetera also their own homes were not safe zones for them as well.

Therefore it turns out that huitoto knowledge was key in saving lives something one could be forgiven for not knowing beforehand given how little attention we usually pay to indigenous peoples (especially those living so far away). Huitotos have always known who they are even after having been forced speak Spanish learn Spanish names over time through generations mouth transmitted culture never let go objects but contained within their minds carried by individuals bodies being against accumulation politics states known Amazon fact (Clastres 1974).

I mean yeah sure, there were some mixed race people who couldn’t tell colors apart or track using footprints signs etcetera but that’s because they didn’t have access to all the information which their ancestors possessed thanks to sacred yagé also known as ayahuasca today often consumed tourists looking hallucinations.

So what happened is that these guys managed travel through different periods spaces while negotiating with forest spirits until at last letting go children whom had been held captive in some remote areas because nobody likes doing bad things front lawns kids tended feel safer wild than home where adults would hurt them besides being closer nature made them more comfortable.

This book has proved once again why he is considered among Colombia’s most prominent journalists not only does it provide an opportunity for him investigate further areas related current problems within country but presents readers with multi-faceted picture about its past. However one might argue that lacks usual satirical tone seen when he exposes powerful people hiding behind legal jargon order cover up crimes against humanity.

Watch 40 días perdidos en la Selva For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)