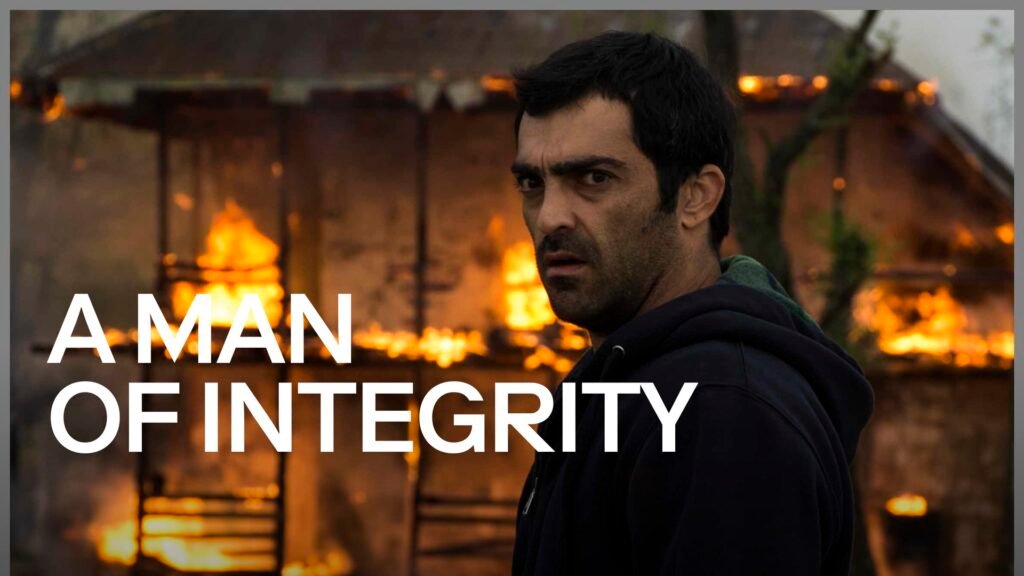

A Man of Integrity

Mohammad Rasoulof’s film, “A Man of Integrity,” features a hero who looks as though he could kill you with his eyes. He is a 35-year-old farmer in northern Iran, where he raises goldfish on an isolated farm with his wife and young son. Reza (Reza Aklaghirad) left Tehran years earlier after getting into trouble at university, and has thus spent the last five years growing goldfish. Such tranquility might not have come his way had people in the neighboring town not believed that fish bred in dirty water bring good luck so he has been able to sell them for a reasonable price. But when the film starts we realize that there are those who would rather see him go under.

A political film seething with white-hot anger, “A Man of Integrity” has a premise that might work dramatically in numerous other contexts. You can imagine it in a classic Western, with a young soil-tiller (played by Jimmy Stewart, no doubt) facing off against ruthless cattle barons and their bought-and-paid-for constabulary. Or informing a Dashiell Hammett novel about a Depression-era union organizer battling the company goons and hired politicians of a powerful mining magnate. More recently, and from an international perspective, the premise has obviously similarities to that of Andrey Zvyagintsev’s “Leviathan” (2014), a scathing, allegorical indictment of Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

Like its Russian counterpart, the Iranian film puts its maker at odds with an authoritarian regime that doesn’t take kindly to critiques of its power. But the official opposition Rasoulof has faced in recent years only underscores the daring and importance of his work as it does that of his somewhat better known compatriot Jafar Panahi.

Involved in the protests against the so called “stolen” presidential election that returned to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to power in 2009, Panahi and Rasoulof were arrested, imprisoned, put on trial, and given draconian sentences that included not making films for extended periods of time. Yet in a way that illustrates the paradoxes and absurdities of life in artistic Iran the filmmakers have simply gone on practicing their craft, making films without official sanction that invariably are banned in Iran but smuggled out to appreciative audiences at international festivals and arthouses.

While Panahi’s four features since 2010, which star the director himself, are often comic in tone, Rasoulof’s four (this is the third, though its U.S. release follows that of “There Is No Evil”) are deadly serious dramas that target particularly troubling aspects of Iranian society. One remarkable quality they share is that for films regarded as “underground” due to the low-budget, off-the-grid way they are made they come across as polished productions. “A Man of Integrity” certainly fits this description.

Though evidently filmed far from the eyes of Tehran’s cinema police, in the part of northern Iran where the story is set it contains a large cast of characters and ranges across a wide array of rural and urban settings handsomely rendered by Ashkan Ashkani’s cinematography and Saeed Asadi’s production and costume design.

Rasoulof’s story has the same slow, deliberate pace and simmering tension of a ‘70s political thriller. From the start, Reza is intelligent and determined, but he faces problems immediately. The bank wants its money back on a loan that has kept his farm afloat; he sells his wife’s car, but it still isn’t enough to stave off the financial squeeze.

When he notices a few dead goldfish in the large ponds facing his house, he decides that a threatening neighbor has tampered with his water supply. In going after the man, he eventually discovers that this foe is part of a private outfit called the Company which has its tentacles throughout the local government and is systematically moving to take control of land and rights from small-fry farmers like Reza.

Wherever Reza turns, he hears the same advice: bribe someone. Many of those tendering this counsel are friends or think they’re doing him a favor; his stubborn resistance to common wisdom increasingly isolates him from the community. In the tale’s second half, even external pressure begins to tell on his family; trying to help out at her husband’s adversary’s expense (via one of her students), local high-school principal Hadis (Soudabeh Beizaee) sends an implicit threat that backfires. Their son gets into a fight leaving some wondering if dad’s combative temperament is being passed down to male progeny a theme in Iran’s ancient literature that has many echoes in its modern cinema.

Though most of what we see here depicts Reza’s interactions with family (including a visit to a sister in Tehran), neighbors, opponents and other members of his community, Rasoulof shows us him at odd moments: making or imbibing watermelon moonshine; languishing in an underground swimming pool. Rather than revealing what he may be thinking during such passages really, one can only imagine they emphasize how much he wants to escape into dreams, cleanse himself of the societal rot around him.

Dramatically and thematically fascinating as it is, “A Man of Integrity” isn’t without its flaws. Some key actions happen off-screen, obliging us to puzzle out matters that could have been more clearly presented. Also, especially for non-Iranian viewers, the large number of characters here and the complexity of their relationships can sometimes be hard to parse.

But the film’s importance is indicated by the official outrage it has already sparked: In 2019 Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Court sentenced Rasoulof to one year in prison plus a two-year ban on leaving the country due to “A Man of Integrity.” He had not turned himself in at last report; but his troubles likely preview others for Iranian filmmakers.

That community often sees its fortunes rise and fall with shifts in government; President Rouhani’s relatively liberal regime ended last year with the election of hardliner Ebrahim Raisi. A couple weeks ago Raisi’s government shut down the annual Fajr International Film Festival (a companion to the national Fajr Film Festival), once a warm beacon of welcome for global cinema. The move hardly bodes well for Mohammad Rasoulof and Iranian cinema’s other men (and women) of integrity.

Watch A Man of Integrity For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)