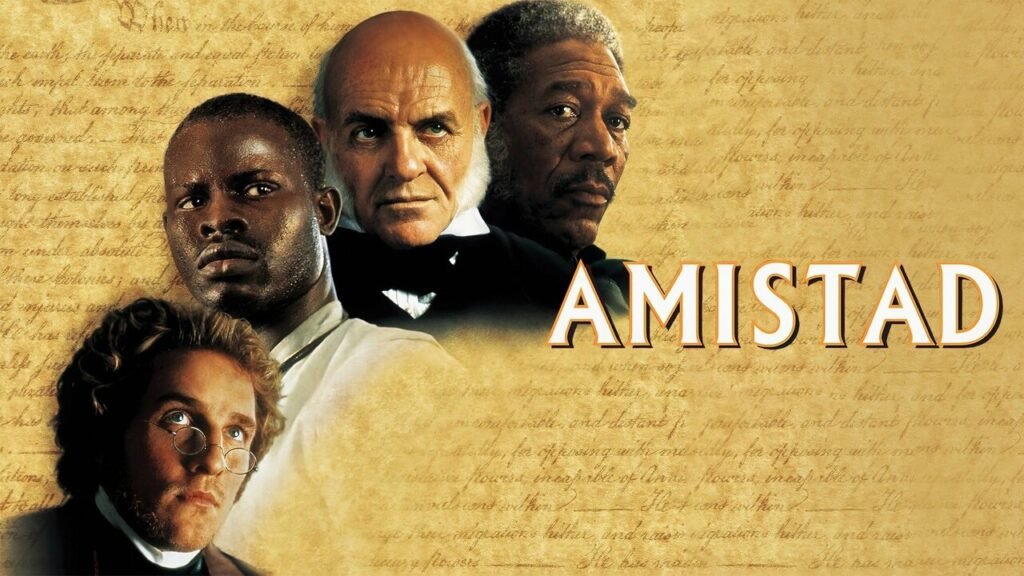

Amistad

As far as I can tell, slavery is mostly a question of laws and property–at least to those who benefit from it. One of the more startling facts revealed in Steven Spielberg’s “Amistad” is that seven of the nine U.S. Supreme Court justices in 1839 were southern slave owners. This new film centers on the legal status of Africans who, in 1839, were captured by slave traders, taken across the seas to Cuba and sold as slaves; they seized their captors’ ship and tried to return home. The issue is not whether they are slaves (their condition is never questioned), but whether they were born slaves (and thus guilty of murder) or were illegally kidnapped from Africa (and thus had a right to kill their captors).

The film does not make this distinction clear enough; in 1839 the international slave trade had been outlawed by most treaties, including one signed by Spain, which should have intercepted “La Amistad,” the slave ship, before arrival at port; but once enslaved, Africans remained their owners’ property and so did their children. The moral distinction between these two states can hardly be imagined without resulting in convulsions; yet on this rests Cinque’s defence.

At first a victimised passenger on board La Amistad bound for slavery in Cuba where he was expected to work for Spanish plantation owners along with his fellow tribesmen kidnapped on African soil during peacetime raid led by other Africans employed by Europeans seeking cheap labourers ,Cinque(Djimon Hounsou) later became leader among them when he managed overpower his captors after freeing himself from chains while still being transported under sail across Atlantic ocean towards western hemisphere.

In revolt against crew members responsible for transporting them becomes aware that two out four sailors bought over counter meant guiding back Africa per route sales agreement between seller representatives buyers involved transaction however they change course once inside US waters eventually leading to their arrest.

Had it not been for the fact that this trial took place in a northern court, the Africans would have had no hope at all. Their defense is hampered at first by a lawyer named Baldwin (Matthew McConaughey), who is interested in property law and almost ignores the human aspects of the case; he is aided, however, by Joadson (Morgan Freeman), an African-American abolitionist, and Tappan (Stellan Skarsgard), an immigrant from Norway. In due course former President John Quincy Adams (Anthony Hopkins) argues eloquently for their freedom before the Supreme Court.

“Amistad” is not like Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List,” just an argument against immorality. We do not need movies to teach us lessons about slavery or the Holocaust. They are both films about good people trying to work within bad systems to help some of its victims but Schindler’s methods are risky and exciting, while those used in “Amistad” by lawyers in powdered wigs are based on legal strategies and language interpreters whose effectiveness must be taken on faith.

Apart from any questions of morality involved, therefore, “Schindler’s List” makes a better story since it involves dangerous deceptions; whereas “Amistad” seeks after truths which if found will be cold comfort for millions still enslaved today so I’m afraid this one didn’t move me as much even though had same director like previous two mentioned above!

The most emotional parts of “Amistad” are those which do not form part of the story proper: a shocking glimpse into what happens when food runs out on a slave ship and the weaker slaves are shackled together and dropped overboard to drown, thereby leaving more food for the others; a scene showing how some Africans capture members of enemy tribes and sell them as slaves to white traders (the mechanics of this process are carefully gone through); Cinque sees some African violets growing in John Quincy Adams’ greenhouse and is struck by homesickness; he remembers his wife back in Africa.

What sets “Amistad” apart from most other movies about African characters is that it gives them names and faces instead of treating them as faceless victims. We see Cinque, not just as an anonymous captive but as an individual with powerful feelings he used to be free once upon a time, when he still had his family around him; we also get glimpses of his wife, village etc., so it becomes clear how much was destroyed when he got torn away from there without any hope or reason (this last point seems particularly sad since slaveholders always did their best to break up black families).

He can’t speak English well but picks up some during his stay in prison; eventually someone finds a translator who helps him complain about such legal systems which may let him go but won’t admit what really happened. By learning bits about our culture too, Cinqe starts seeing its contradictions one day another inmate shows him pictures from Bible stories where people like himself suffer alongside Jesus Christ whom they both resemble physically; moreover lawyer-client conversations between Joadson finally become human rather than puzzle-like exchanges. “Give us free!” shouts Qinsay during trial having realized that finding out whether you’re guilty or not doesn’t mean anything if nobody cares why you should’ve been there anyway.

Djimon Hounsou’s performance in “Amistad” relies heavily on his presence alone, which is very strong indeed. Some of the other actors seem less committed, however; for instance I felt that not enough effort had been put into developing Morgan Freeman’s character or giving it enough screen time (although even so, through what little we see him say and do one can sense volumes left unsaid). Matthew McConaughey plays a defense attorney whose role necessarily lacks focus: he starts off blind morally but soon has revelation at which point nobody feels surprised although glad but not much moved given surrounding circumstances.

President Martin Van Buren as played by Nigel Hawthorne comes across like an appeaser who wants only to pacify the South without getting involved himself this interpretation works fine if you’re performing George III but for someone with more cunning might have worked better in “The Madness Of King George”.

It must be said though that Anthony Hopkins’ tour de force performance steals all hearts from everybody else including mine – old John Quincy Adams speaks 11 minutes defending those poor souls on trial while holding court spellbound (what could’ve been a great speech becomes one because there are no competing good ones). However, herein lies another problem: too much law talk, not enough about victims!

Since Spielberg started “Amistad,” the story has been built up and praised as a forgotten chapter in American history, another Nat Turner’s rebellion. Cinque’s story should certainly be covered more by textbooks, but it is not the best one to adapt for film; Spielberg should have chosen Nat Turner. That he wins his big case is John Quincy Adams’ great achievement and Cinque’s fellow prisoners’ great relief; however, in the unhappy records of American slavery, it remains rather an empty victory.

Watch Amistad For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)