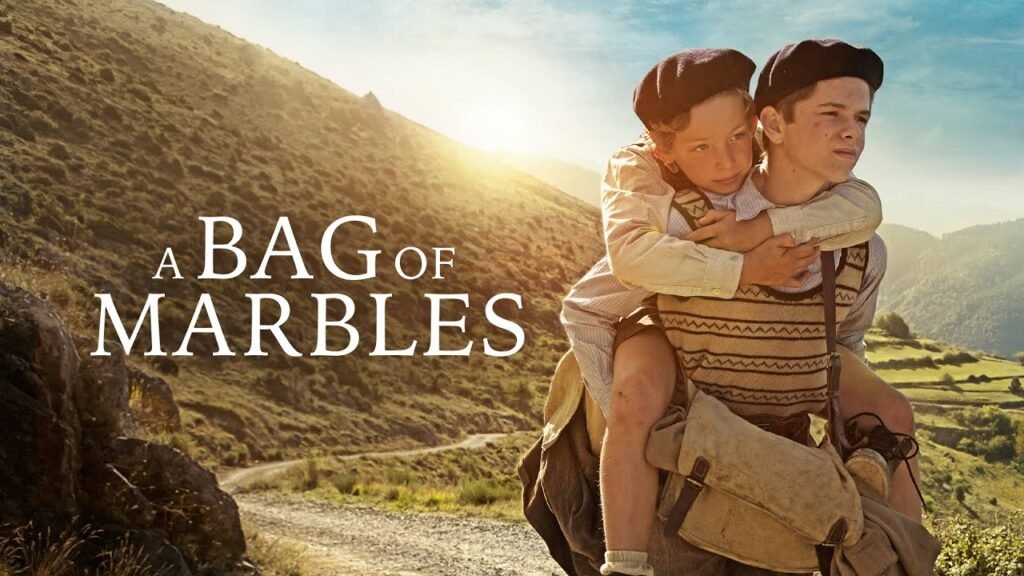

A Bag of Marbles

At some point, films regarding the Holocaust were being made with a deliberate effort to keep history alive for future generations. As a research paper for my junior high school history class, I analyzed three movies that describe the impact of Nazi atrocities from remarkably different perspectives the advance fear of Anne Frank’s family hiding in George Stevens’ “The Diary of Anne Frank,” the graphic horrors of a concentration camp in Steven Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List” and the abominable denial by Nazi judges on trial in Stanley Kramer’s “Judgment at Nuremberg.”

When I was young, this informal trilogy informed me about what terrible evil human beings can do when they are consumed by hatred. Critics have often condemned Spielberg for having turned his cameras away from the millions who died and towards those who somehow managed to survive but it is hard to forget the senseless killing shot like newsreels by Janusz Kaminski that I remember so vividly.

That which cinema once sought to remember cannot be forgotten now because there are politicians who gain their power through exploiting fears and cultivating hatreds among voters. Always these holocaust films were teaching us about our past as well as our present, and that has never been more evident than during the aftermath of last August’s white supremacist rally in Charlottesville.

The great thing about Christian Duguay’s “A Bag of Marbles” is how much it helps young people to understand a very violent and confusing episode in human history. Yes, the film tells the story of real human beings who managed to survive but that does not make their suffering less terrible. It’s based on Joseph Joffo’s memoir of 1973 about his own experiences as a teenage Jew in Nazi-occupied Paris which was later adapted by Jacques Doillon into a film shortly after its publication with an aim at achieving what Joffo himself called a more “truthful” account of his growing up years in occupied France.

It is not going to be one of those slow moving sad songs that puts you to sleep while seated on your chair in class under dim lights. I think any 12-year old should be glued to this movie for the full two hours, which has moments full of tension and terror where they are supposed to, but also light heartedness which doesn’t feel fake. The vast majority (sic) features ten year old Joseph (Dorian Le Clech), and his twelve year old brother Maurice (Batyste Fleurial), fleeing their home in Paris for a “free zone” in Nice.

Duguay and his screenwriters allow these characters to behave like actual children instead of miniature adults, even as they’re forced to grow up much faster than they would’ve preferred. We can never predict when humor and miracles will come knocking into our lives, so let us see what happens when Joseph and Maurice go on their journey; anything that diverts attention from their dire situation is welcomed whether it means playing amid the sunlit meadow or horseplay between brothers. Armand Amar, who also composed “Belle & Sebastian,” another film about children outwitting Nazis adds immensely to this tone.

We first meet him/it/her while he/it/she is escaping with his/its/her brother Maurice (Batyste Fleurial), as they run away from their home in Paris to a “free zone” in Nice; he/it/she is usually very still. This shot is quite like the one at the beginning of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban when the train carrying Harry to Hogwarts is attacked by an evil dementor that seemed so much like a Nazi officer.

Other touches are downright Spielbergian, ranging from faceless men with predatory light beams in a forest to American planes flying over rooftops heralding victory for our heroes. Even more gloriously was this uplifting scene shown in Steven Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun which recounted another true story about a young boy who lived through war by hiding from Japanese forces during WWII. Just like 13-year old Christian Bale’s debut performance was pivotal for ‘Empire’, so does Le Clech’s great work serve as an emotional anchor here.

He never forces his acting to be over sentimental just to score some points on your emotions. His eyes too often well up with tears and then he struggles to keep them back, for instance, when his father, Roman (Patrick Bruel) has had enough and must resort to violence as a means of teaching his sons an important lesson.

Roman’s youthful experiences of surviving anti-Semitic pogroms in Russia make him aware that he has to harden his children against pain if they are not to die by not getting hurt at a later date. He wants Joseph to be ready for Nazi interrogations and while demanding whether the boy is Jewish, he keeps slapping him repeatedly. Such a moment of improvisation and neediness was no less important than when Roman’s wife Anna, played by Elsa Zylberstein, talked her family out of a corner by objecting to a Nazi who accused her of playing Jewish music on her violin.

Since Joseph’s father does not appear very friendly in the beginning, one may think that Bruel is aloof; however, this coldness emanates from his desire to remain strong for his family. Two scenes in particular had me most emotionally moved out of all others: First, when Roman prepares himself to leave his sons again for another long time. It was only after he turned away from them did I get to see his face crumple in hopelessness.

Similarly memorable is the sight of Roman in the back seat with both boys sleeping on either side, their heads resting on his shoulders. Everything about this shot is hauntingly bittersweet as the father savours this isolated moment of peace before their world invades them again. Like its individuals “A Bag of Marbles” rolls between different locations as they rely on strangers while still having reservations about keeping themselves safe. There are instances where several side characters have been portrayed vividly like real people including an SS chief who progressively shows obsession towards these two kids and two men playing good Christians who would defend those kids as if they were theirs.

A notable instance happens at one point when Gajan could have held a shot for an extra beat longer before cutting onto the next scene because he has experience with music videos as an editor. Their first reunion with their parents happens so quickly and is so bright that I thought it was a dream sequence; and in a way, it is one depicting the unachievable tranquility that those people cannot have together. At times, you may be lulled into complacency by contentment before malevolence shows up out of nowhere in one case, as silence that wears on until it becomes nauseating.

The most powerful of Gajan’s edits are those in which he heightens tension with short cuts, emphasizing the dire need for every second to count for these characters e.g. when Joseph notices danger approaching which otherwise would have escaped his attention because of sunlight peeping through clouds.

Other critics over the years have questioned whether Joffo’s story had always been told right or he exaggerated some events after several years passed. Even though “A Bag of Marbles” might be more fictional as history goes, this aligns it with great parables like “The Sound of Music,” having much significant altitude gain.

Duguay’s film is a very good historical drama for most of its duration until the final act, which makes it almost great. Le Clech captures his character’s bravery perfectly in the face of a Nazi who beats his brother but he doesn’t back down from slamming one into a lamp either. Joseph prays not to God or any other imaginary power but to himself saying “I’m tired of this now” all the time. The swastika flags are pulled down off houses in Paris and French people start attacking Nazi collaborators and then Joseph does something that is so innocent and heartfelt that I found myself clapping my hands for him.

It was like when his father made a play on words with his hand at the beginning of the movie just to show Nazis they were people too. After watching this movie, I realized that what Joseph did at the end was just an extension of what I had always tried to live by-as continually corroborated by contemporary heroes like Malala Yousafzai, Emma González and Sonita Alizadeh. One thing however I am sure of nowadays is that our only hope lies with these young ones speaking what they believe in their hearts.

Watch A Bag of Marbles For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)