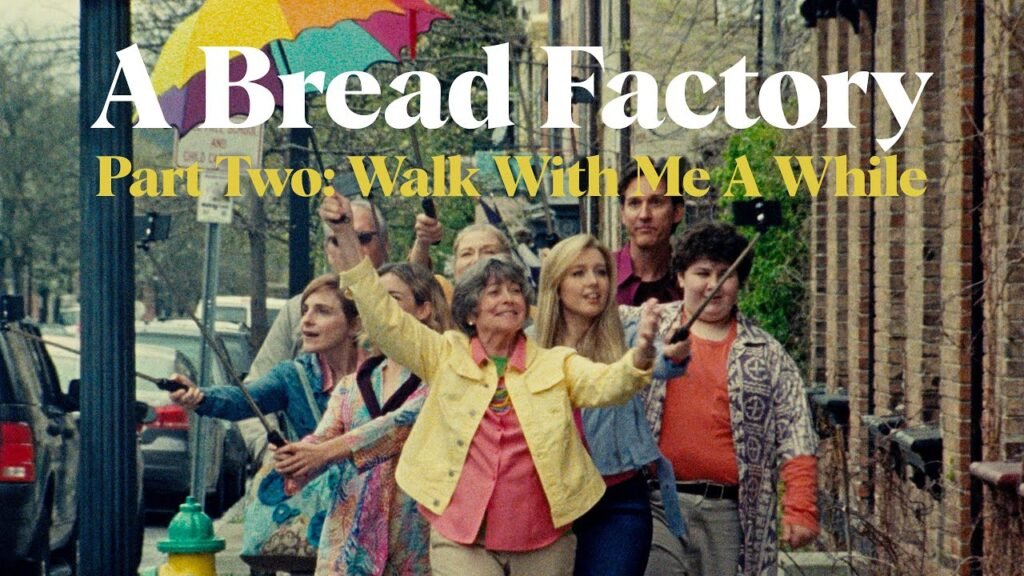

A Bread Factory-Part Two

[Editor’s Note: This review covers Part Two of “A Bread Factory,” a two part film about the impact an arts center has on a small town in upstate New York. Written and directed by Patrick Wang (“In the Family”), each part stands alone as its own feature but they are designed to be seen together. To read the review of Part One, click here.]

Part Two of “A Bread Factory,” an unhurried epic concerning the efforts of a small town art center to keep going, is just as meticulously constructed as Part One, but lighter on its feet and more fun. The first movie mixed conversations and confrontations with snippets of art shown at the Bread Factory itself or a rival establishment across town; for the most part, it was clear which parts were “real” and which weren’t.

That line blurs throughout this one called “Walk With Me a While” which takes up where Part One left off in some scenes while spinning out into wild flights of fancy (some charmingly goofy) in others. It shifts between ensemble comedy, domestic melodrama, musical and filmed play so freely that it often plays like an anthology film held together less by story than by theme.

Part Two begins with the same Trooper James scene from Part One. He spills something on his shirt and pulls it off casually, looking wryly into the camera at the end of the scene. Patrons turn away, as if not having ogled him. It’s a Ferris Bueller or Bugs Bunny gesture of cheekiness in a film that otherwise lets us feel like we’re being a fly on the wall to people who don’t know we’re there.

So Part Two gives us more play within a play scenes where we watch people act in productions. It has musical numbers staged in the spirit of an “everyday” movie musical ordinary people bursting into song and dance in real locations and even has scenes where people behave as if they’re in a stage play or movie musical when they’re out in the world, “reality.”

The setting is still Checkford, New York. There are two arts centers in town: one is a 40-year old facility run by a veteran married couple (Tyne Daly and Elisabeth Henry) out of what used to be a bread factory; and another across town that’s newer, better-funded and more connected to much slicker art (it’s run by a couple of hipster performance artists who go by the team name May Ray (Janet Hsieh and George Young) and their administrator Karl (Trevor St. John).

The narrative picks up after Part One left off with the Bread Factory having just narrowly avoided closure after surviving years of threats from politicians, real estate developers and school board members who would kill for its space; this time around, the school board actually did take away their education subsidy grant but then didn’t give it to May Ray because somebody found some report somewhere that said giving it to them would be illegal for reasons no one seems clear on yet but you can bet there will be lawsuits all over town about it soon enough or maybe not because this is Checkford.

And so as it turns out our intrepid gang of artists, actors, educators and loyal patrons aren’t quite out of the woods yet there are more scenes depicting the center’s continued fight to survive and stay relevant in an age where everything is a “platform.” There’s also a subplot about the local newspaper editor Jan (Glynnis O’Connor) suddenly disappearing and leaving her paper to a talented young intern Max (Zachary Sale) who’s in violent rebellion against his self-involved and unfaithful father (James Marsters).

What I find most shocking and difficult to understand about the second part is how it takes one of the main ideas from the first part that art can help us understand and express ourselves in everyday life and makes it external so that creativity, which could have remained confined to stages or arts centres, erupts into the world.

A quartet of singing characters who work for a local estate agent arrive at Dorothea (Daly)’s office, one of the co-founders and bosses of The Bread Factory, asking her through song to stop fighting, sell a barn on her land currently being used for set-building, and go travelling with her partner Greta (Elisabeth Henry), Checkford’s Isabelle Huppert.

A coach load of tourists gets off outside The Bread Factory and wanders around town taking selfies while a tour guide tells them nonsense ‘facts’ (“This is the place/Where God was invented/Where Adam and Eve dated/Each other!”). Customers sit at tables in a local restaurant talking in groups or texting alone; suddenly a young man starts doing a tap dance routine in time with his fingers as he types on his phone.

There are other dance numbers like this, but they’re not just indulgences: they’re plugged into one of the organising ideas of the movie that artists need to understand and adapt to a changing world. Tourists filming themselves during a walking tour shows how iPhones and social media enclose us in bubbles of narcissism; those bubbles shut us off from physical reality as well as from having to talk to strangers. But at the same time social media turns us into bold and confident performers who develop our own aesthetic on a virtual public stage: like actors appearing in The Bread Factory’s production of Hecuba, getting better the longer they do it.

Even seemingly ordinary scenes of people hanging out feel more theatricalised and pointed in this half of the story more indicative of how art informs life, and how the two bleed into each other so that it’s sometimes hard to tell where one starts and the other stops. Sir Walter (Brian May), the old English actor who has starred in many Bread Factory productions, hangs out at the newspaper office, mourning his friend Jan’s disappearance and watching Max train a small army of children (all regulars at The Bread Factory) to be journalists (delightful comic scenes, like something out of an early Wes Anderson film).

He is unexpectedly joined by the local writer Jean-Marc (Philip Kerr), whom Walter hasn’t spoken to since he panned one of his performances in 1968. They swap stories told as long theatrical monologues, and come to understand one another. The camera holds on their faces as they talk and takes us inside their heads. In these scenes, and in others set on an actual stage, Wang channels Bergman, who kept finding new worlds in close-ups of people talking.

A more traditional approach to public art is shown in the scenes of “Hecuba” rehearsed and performed. Teresa (Jessica Pimintel), a waitress at the cafe, plays Greta’s character’s daughter, even though she has never acted before. (Every citizen of Checkford eventually appears on the stage, we’re told.)

Wang gives us a long scene of Teresa struggling through a read-through while Dorothea directs her and Greta gives her an acting model to emulate. Like in Part One’s closing scene where Max reads aloud from “Hecuba” in distress, loses his self-consciousness, starts finding solace in the words we see Teresa come alive as an actress. She becomes the character by letting the words and her scene partner’s performance flow through her.

This is something that actors talk about all the time but you almost never see it happen right in front of you, in real time. Teresa becoming an actress is this film’s true heart, as delicately observed as an athlete’s training in a sports movie; it culminates in a daringly long sequence at the end as long as Part One’s school board hearing where Wang simply lets us watch a wrenching scene from “Hecuba” being performed by Teresa, Greta and another Bread Factory regular (Jonathan Iglesias).

We not only see that Teresa is a real actress; we understand how “Hecuba” characters’ fears mirror those of “A Bread Factory” characters (especially Dorothea) that their beloved arts center will be taken away from them. We never see the audience during this sequence but we can imagine ourselves sitting there in the theater watching this play while thinking about what will happen to Bread Factory and town?, what is art for? why do people make plays?? how should I live my life????

Part Two of “A Bread Factory” can be discombobulating if you haven’t seen Part One. You have to intuit a lot of the story because it’s shown in (and hinted at by) the countless scenes where people are acting. But it can be enjoyed on its own, as just a bunch of moments where a filmmaker and his cast go for broke, not caring whether we’re going to buy every single thing they do.

And if you watch them together, it seems like as complete and thoughtful a statement about life and art as any movie ever made. Part One is life; Part Two is art; there’s plenty of overlap in either half; and they balance each other out so that we think about our lives next to the art we love and Wang’s movies become mirrors that scare us while making us dream.

Watch A Bread Factory-Part Two For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)