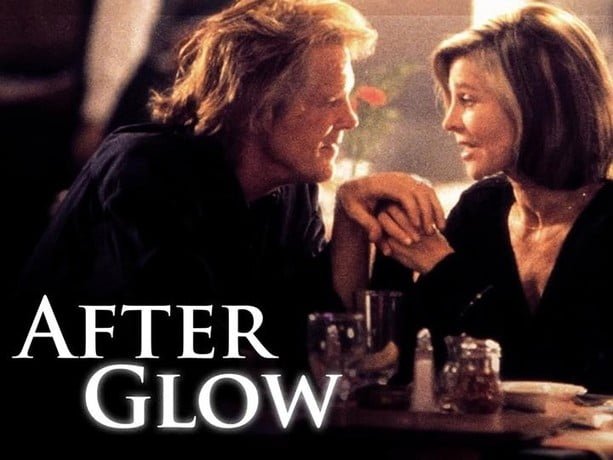

Afterglow

On the covers of romance novels or the poster for “Doctor Zhivago,” Julie Christie faces such as this are made. She has that wounded perfection of a great beauty who has had all the wrong luck. In “Afterglow,” her third film in the 1990s alone, she plays a character that she must know inside out: Phyllis Mann, a former B-movie actress specializing in horror roles, who lives in Montreal with her husband Lucky (Nick Nolte), a handyman well versed in wrenches and wenches.

A great sadness from their past hangs over them; they cling together with love and understanding, but he philanders among lonely housewives who phone him for plumbing repairs while she looks the other way (“Plumbing and a woman’s nature are both unpredictable and filled with hidden mysteries,” he philosophizes).

But Nolte’s Lucky is not so much a sex machine as a gentle man whose eye for women comes out of some deeper sympathy his wife tells him he can fool around as long as it doesn’t get serious and one day seriousness appears to threaten when he meets Marianne Byron (Lara Flynn Boyle), a yuppie wife who yearns for the baby her husband will not give her (or cannot give her). So desperate is this need that Marianne has hired Lucky Mann to convert an extra bedroom into a nursery even as her cold, arrogant husband Jeffrey (Jonny Lee Miller, Sick Boy from “Trainspotting”) vows that children have nothing to do with his plans.

The plot by this point might sound like soap opera material, but there is always something off kilter about an Alan Rudolph movie, strange notes and touches that keep everything at arm’s length below painful flashes of human nature. Imagine if you will a soap opera where characters subtly make fun their own parts while actors occasionally break down weeping about their lives far away from the soundstage.

“Afterglow” has, yes, a script that allows for coincidence and contrivance; like many of Rudolph’s films (“Choose Me,” “Trouble in Mind”), it features characters who seem somehow fated to share common destinies. As Lucky Mann falls into the pit dug by Marianne’s great need, Phyllis meets Jeffrey and allows herself to be drawn toward him out of curiosity and vengeance mixed.

But what makes “Afterglow” work is not so much an evident style as some of Rudolph’s other movies have depended on but rather its story; he wrote it himself and seems so involved with it that directorial remove was unnecessary. That may be because the characters are so strong.

Julie Christie, lying on a couch watching her old horror movies, has monologues where she looks back at Hollywood with the wonderment of a crash victim. And Nick Nolte’s character isn’t just a louse; his sex life could represent a profound understanding for women which is also where his sympathy lies for his wife, whose very being appears soaked in sorrow.

What’s the matter with Christie? I know her from way back when: “Darling,” “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” “Far From the Madding Crowd,” “Shampoo.” But then what happened to her career? She started making all these inconsequential movies nobody remembers seeing.

Every once in a while she’d give an interview to the paper, saying how happy she was alone. Like Phyllis, she puts some distance on those early years; but Phyllis uses that distance to make something new and fragile here. You know how sometimes a performance can be just mysterious?

Watch Afterglow For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)