Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq

Most ballet documentaries, even the best of them, inevitably cater to dance lovers. “Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil le Clercq,” by Nancy Buirski, is an exception. It profiles the work of a brilliant dancer and contains two love stories as well as one physically devastating tragedy and one extraordinary story of survival.

Tanaquil le Clercq was both muse and lover for two of America’s greatest choreographers George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins. Born in Paris in 1929 and brought up in New York City in privilege and some degree of isolation, she began to study dance as a child and was at Balanchine’s School of American Ballet when he discovered her. He cast her in lead roles though she was only 15, and she became a star overnight, never having served an apprenticeship the corps de ballet.

The director includes clips that show what a skilled dancer le Clercq was, but also makes it clear that her career benefited from her appearance. In an era when ballerinas were short, she was tall, long-legged and coltishly energetic on stage; her face had a unique combination of simplicity and ethereal hauteur Julie Harris with angles plus Lauren Bacall’s insolence.

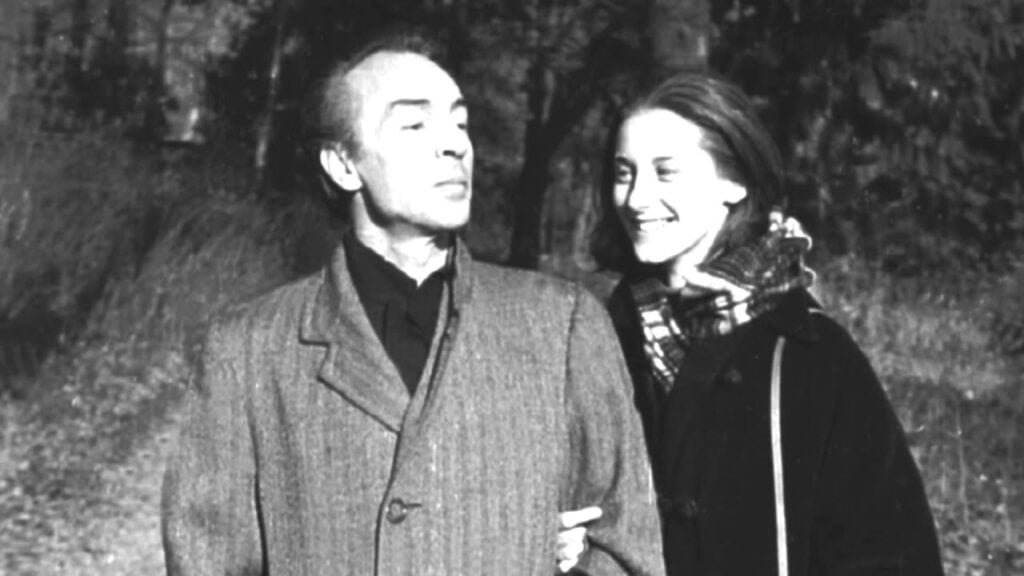

Balanchine had depended creatively as well as romantically on his prima ballerinas since his middle age (he was past 40 when he met Tanny); four had married him before they left him (rather than the other way around) because their artistic partnership seemed to have run its course. With Tanny that pattern merely repeated itself, but according to everyone who knew them both sides loved deeply; they married in 1952.

Jerry Robbins was older than Tanny by several years but had been infatuated with her since they’d met; he said she was the reason he joined New York City Ballet upon Balanchine’s invitation. The most moving parts of the movie are the excerpts from letters between Jerry and Tanny (read by actors), which show a complicated mixture of friendship and romance, one that was bound to leave him enthralled and frustrated; he seems to have been crushed when she married Balanchine.

In 1956 the company went on a European tour at a time when polio was scaring half the world. Most of the dancers took the new Salk vaccine before they left; Tanny decided not to at the last minute. She got sick in Copenhagen, was put in an iron lung with expectations that she would die but didn’t: She never walked again, never danced again.

The sudden horror of the dancer’s illness and her struggle in its aftermath are where the film’s fascinating chronicle of a talented artist’s ascent turns even more absorbing. It seems, strangely, that while Tanny is tossed about by her change in fortune, her emotions undulating one way and then another, her spirit largely remains the same. And Balanchine is still an ardent champion through her treatment at Warm Springs, Ga., and re-entry into New York; she complains that Robbins is an erratic correspondent, but his letters and photographs make it clear that his attachment to her is as strong as ever.

Those photos make the point that some documentaries need a wealth of material on their subjects to succeed while others can turn a famine into a feast. Here there were only a few Tanny interviews during her career for Buirski to draw on, and none after (le Clercq died in 2000), and the archival footage of her dancing of course came well before HD; fancy production values were not yet invented.

It’s these very limitations, though, that draw us even more deeply into Buirski’s portrait of the dancer. Watching Tanny’s radiant face in Robbins’ eloquent photos or the post-polio Super-8 movies made by friends who just couldn’t stop filming “the wounded bird,” we see we know an absolutely astonishing soul with an insight, a warmth and a generosity that were beyond human. As one of them says, “her regard was all acceptance, forgiveness.”

Ultimately any great film about one person touches upon what makes people tick what makes us human and “Afternoon of a Faun” does so with uncommon grace. Some viewers may come away from this movie wishing they’d seen Tanny dance; perhaps even more will wish they’d spent an afternoon in the park with her.

It should be said here that Buirski and editor Damian Rodriguez do an excellent job of telling their story through interviews and footage of dances that, though old, remain striking. The most hypnotic of all, which opens and closes the film, is from the eponymous “Afternoon of a Faun” piece that Robbins created for Tanny and Jacques d’Amboise. In an old black-and-white kinescope, the dancers perform as in a studio, but with the camera where the mirror should be. Somehow the effect is even more mesmerizing decades later two figures on a bare stage making magic.

Watch Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)