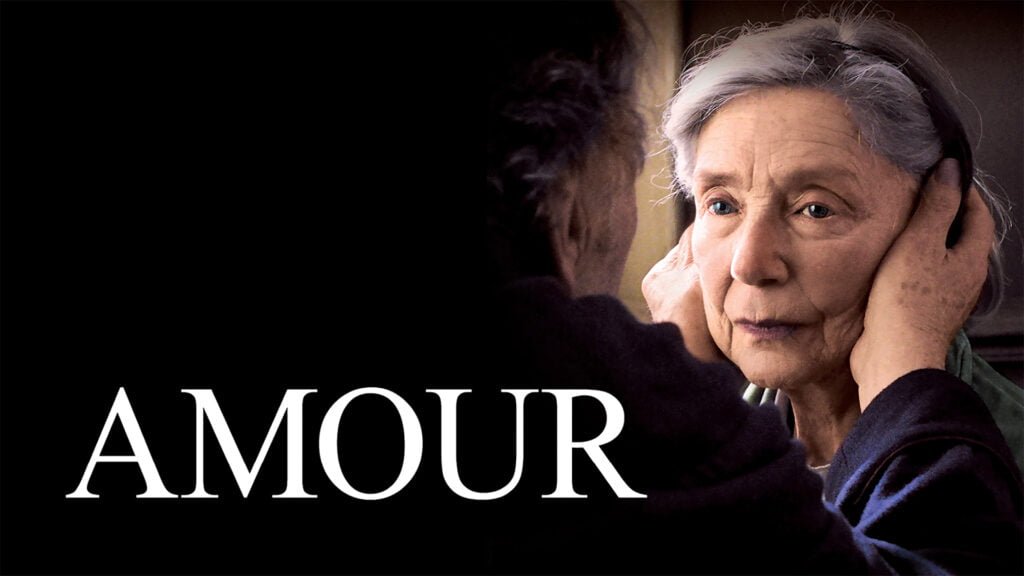

Amour

“Old age is not a place for cowards,” is what Bette Davis said, and the longer it goes on, the less of a coward one can be. The first image in Michael Haneke’s “Amour” shows firemen breaking into an elegant flat in Paris. We do not know who lives there, or anything about them apart from the fact that they are dead, which we learn only when one firefighter holds his nose while standing outside a bedroom door. Inside is the lifeless body of an old woman, surrounded by wilted flowers.

In the end it is just this: earthly remains and memories of beauty grown pale. But that’s only true for outsiders for the deceased and for firemen. For everyone else it’s great to sit in the dark. Another of Mr. Haneke’s very early shots brings us onto a stage looking out at an audience gathered for a piano recital; we never see the stage but here the subject is watching. The music being played is passionate, its performance rapturous and informed: these people know why it’s good because it has been their lot to know lots of things like this.

How did my gaze alight on that particular old couple in the stalls? A film-maker can make us look at something by putting it center screen but here Mr. Haneke was deliberately fair-minded. Still I noticed them: Emmanuelle Riva and Jean-Louis Trintignant (both now in their 80s), two giants of French cinema whom I didn’t recognize at that age (I wonder if any film-goer could have done); so there must have been something about them their self possession, their inner calm; maybe just their being together seemed such an unassailable fact.

They are Anne and Georges; we’ll soon learn that they spent their lives playing music and teaching others to play music. Later still we’ll find out that the concert is being given by a young maestro (Alexandre Tharaud) who used to be Anne’s pupil. In a way, they have brought this beauty into being in their own lives.

“Amour,” which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes last year, is an uncharacteristic masterpiece from Mr Haneke, whose films include the inexplicable “Caché” and the earlier Golden Palm winner “The White Ribbon.” Such unflinching gravity, such profoundness we do not expect from him. Unlike a mystery like “Caché,” which people argue about still though it came out seven years ago, this one is just what it looks like: you cannot spoil it for anyone. The first scene tells you how the last will go.

Now look at Anne and Georges over breakfast a little later on. He doesn’t even notice that she has stopped moving for a moment; her husband actually does not see his wife’s temporary absence from the world. The shots of this section are brilliant. Then she comes back in she never knew she was away but she was; then one day she really will be gone and now things between them can only end badly.

Every scene except one in “Amour” (love) takes place within the Parisian apartment of Georges and Anne. The other scene shows the street outside, seen from their window. They are retired music teachers in their 80s. One day Anne has an attack. Her condition deteriorates. She makes an explicit request to Georges, which he acknowledges but finds hard to fulfill.

That is all that happens, almost not very much for a narrative film. “Amour,” like all of Haneke’s films and many of Bergman’s, is about how little happens until everything does.

Yes, old age isn’t for sissies, and neither is this film. Trintignant and Riva courageously take on these roles that strip aside all the glamor of their long careers (he starred in “A Man and a Woman,” she most famously in “Hiroshima Mon Amour”). Their beauty has faded away; it glows from within. It accepts unflinchingly the realities of age, failure and the disintegration of the ego.

And so yes: We are yet another audience who must accept them, too. When I saw “Hiroshima” in 1959 I was young and eager and excited to be attending one of the first French art films I’d ever seen which helped teach me what it was, and who I was. Now I see that we were carried on along with it because it has meaning for us now as well as then; because we have changed along with it; because sooner or later those firemen are coming looking for all of us.

This is now: We are filled with optimism and expectation! So why would we want to see such a film however brilliantly made? Well maybe that’s exactly why: Because a film like “Amour” has a lesson for us that only cinema can teach: Cinema itself which can leap across time so heedlessly, which can transcend lives and dramatize what it means to be a member of the eternal audience has come along with us.

Watch Amour For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)