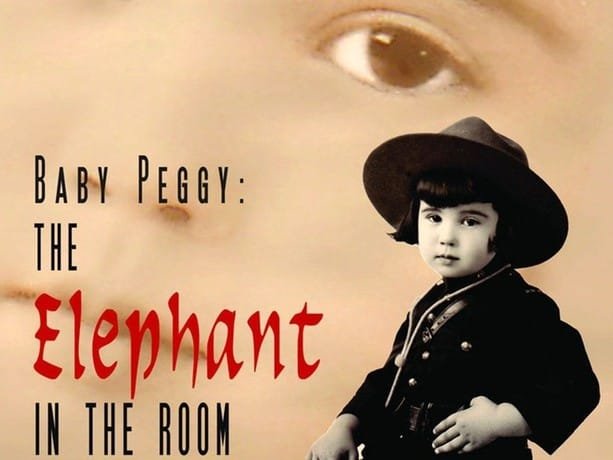

Baby Peggy: The Elephant in the Room

When referring to child stars at present, we think of children aged 9 or 10 and even in their early teens. We have as an example Macaulay Culkin in “Home Alone,” Haley Joel Osment in “The Sixth Sense” and Jayden Smith who starred opposite his father Will Smith in “After Earth.” Nevertheless, during the silent era and the early years of talking pictures, child stars were often little more than babies as their names indicate.

There was Baby Marie, who made her most famous film, “Little Mary Sunshine,” at age five. There was Baby LeRoy, who was given a studio contract at 16 months and appeared opposite W.C. Fields in the classic comedy “It’s A Gift.” And there was Baby Peggy, who in 1920 was discovered aged 19 months and in 1924 earned a million dollars for starring in “Captain January.”

In the first half of the 1920s alone, “Baby” Peggy-Jean Montgomery was a superstar she made over 150 shorts alongside her features. Then she became one of the biggest names in vaudeville. And then she disappeared for decades. Her films were largely lost and her name was largely forgotten.

Baby Peggy is still alive; she is now Diana Serra Cary and is somewhere between her mid 90s and never you mind how old I am thank you very much. She is a writer and historian and has written a study of child actors called “Hollywood’s Children” (which she has subtitled: “From Shirley Temple to Abigail Breslin”) as well as a biography of Jackie Coogan one of the greatest all-time child stars which led to Coogan’s Law being passed.

Vera Iwerebor’s documentary “Baby Peggy: The Elephant In The Room” tells Cary’s story (“narrated” by actress Cecilia Peck) and aims to return her to something like the prominence she deserves in the history of silent film. It is a simple, succinct documentary: less than an hour long and composed principally of archive film footage, talking head interviews with Cary (now 94 years old) and still photographs. (On DVD, the feature is accompanied by the feature-length “Captain January” one of Baby Peggy’s most successful films as well as three of her shorts.)

The woman we watch in these modern-day scenes would be worthy of a documentary even if she had not been Baby Peggy 90 years ago. Diana Serra Cary is a remarkable person energetic, intelligent and at times only able to speak in pithy insights (“I was a blight on their romance,” she says of her parents, “because I put a kind of reality in their life that they couldn’t cope with”).

She has lived for almost a century, but has always had an alert mind and retentive memory. As a child she was remarkably precocious; as a nonagenarian she is remarkably youthful. At least 20 years younger than her age, Cary has the self-confidence and easy erudition of someone highbred and over-educated neither of which she was.

She was the daughter of a cowboy and sometimes a stuntman for silent movies. Her father was very strict and believed that the only reason Peggy became famous was because he had been such a tough parent. But Peggy’s parents weren’t always cruel; they were also clueless. She didn’t go to school, and although she made money, her father spent most of it on things we don’t always know about. After he broke her contract he fought with a Hollywood studio head who refused to pay her for “Captain January” any hope of her continuing in show business ended and the family essentially had to leave town.

She went to work in vaudeville theaters that advertised their child star as appearing all day “in continuous performance.” She hated it, thought of it as a kind of slavery. When talking pictures threatened to put an end to vaudeville, she rejoiced but before long she was back in Hollywood.

She never really made it in talkies, worked as an extra until her father bought a ranch with her earnings and moved the family there; then his mismanagement (and the Great Depression) did them in financially, and they wound up working for nothing on the ranch till they had to give up on it altogether. The career of Baby Peggy literally went unmentioned: It became the elephant in the room.

The broad outlines are familiar even predictable from any number of stories about child stars, but rarely have they been told with such immediacy or intimacy: Few people can ever have contemplated the doom of kid actors as deeply (or from so close by), or had as much reason, which lends Cary’s film a special kind of life that most documentaries about silent cinema can’t even approach. She is uniquely suited among living humans to articulate those experiences.

Baby Peggy is another human being to Cary someone she played, not someone she was and this is understandable given how far apart those two people are (the infant who appeared on screen in the 1920s; the old woman looking back from the 2020s). But what’s astonishing is that she regarded Baby Peggy as a separate person even when she herself was a child. She knew, at 4 years old, what it meant to be Baby Peggy both on screen and off and she knew that being something more (and less) than a child. “I thought I was a grown-up,” she says. “I knew I was the breadwinner.”

Forty years later, she would look at her young son and feel angry with him because he was just sitting there playing on the floor of their house. Why wasn’t he out working? The psychic cost of being Baby Peggy had been severe. By the end of the film we don’t see Diana Serra Cary as an actress or an historian; we see her simply as someone who made it through.

Watch Baby Peggy: The Elephant in the Room For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)