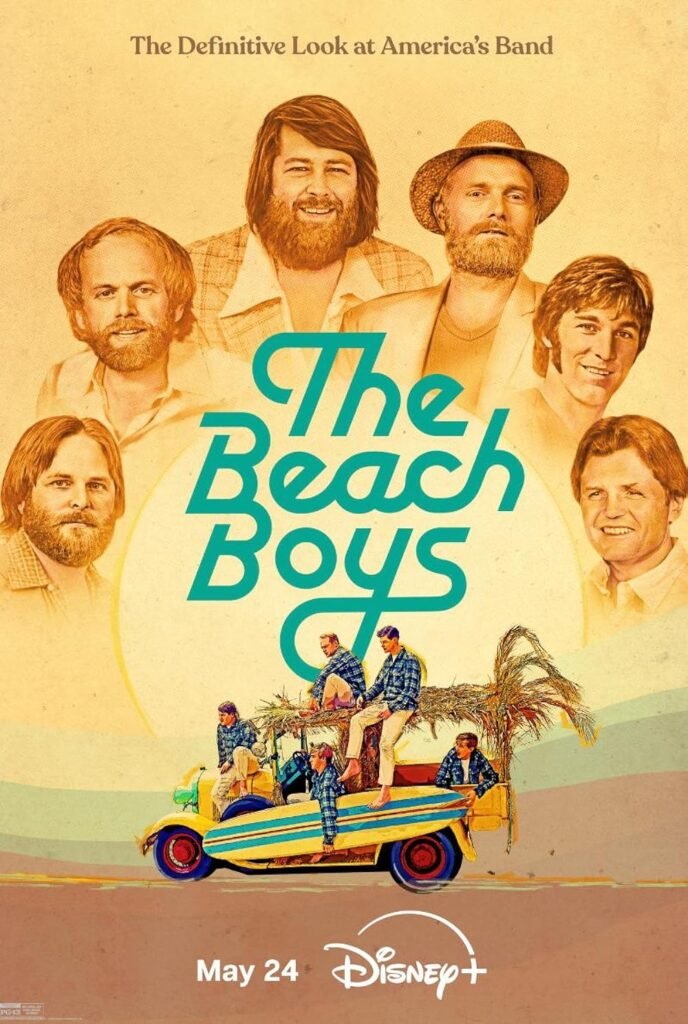

The Beach Boys Review

Among the early moments of this Disney rock documentary is a moment that speaks volumes. It’s July 1976, the year of the US bicentennial, and the Beach Boys are taking a stage before thousands of cheering fans in Anaheim, California. This is, ostensibly, a moment of triumph for “America’s band”, as they have just been called by an announcer. Their commercial fortunes have been revived over the past couple of years by a chart-topping compilation of their early hits called Endless Summer; and their errant genius Brian Wilson has reportedly returned to full health after years lost to drug abuse (“BRIAN IS BACK!” claims a promotional campaign that summer) and mental illness (he spent most of 1967 in bed). “I like it, I like it,” says frontman Mike Love, looking out at the crowd and well he might. Then we cut to Wilson, his face a mask of confusion and fear suggesting that reports of his return may have been premature; he does not seem to be liking it much at all.

The Beach Boys were never quite who they seemed to be. Frank Marshall’s documentary is good on the contrast between the myth of gilded Californian youth that their music sold to the world and the reality behind it. Singing about an impossibly sun-drenched utopia of health, beauty, confidence and endless material luxury in one vintage television clip after another, they look awkward nothing like these tanned young gods but who cares? The songs were so good! Brian Wilson’s harmonies! The songs themselves poured out with such astonishing frequency that no one ever asked where he was getting them from. “Even when I didn’t get what I was singing about myself” which was most often “I still sang my ass off,” chuckles Bruce Johnston. A lot has been made lately about how quickly those first few albums came together: four in 1964 alone (one of them a Christmas album) plus two more in 1965 and, somehow, another three on top of that. “We were trying to get rich quick,” shrugs Johnston; they were also trying not to be drowned out by the Beatles. But why would they have been? They were the Beach Boys!

The childhoods of Brian, Dennis and Carl Wilson could hardly have been further from the world their music sang about. Their father Murry was a mentally and physically abusive monster who terrified his wife and children; in one old interview clip, Dennis and Carl grimly recall the different-sized pieces of wood he had for beating each son. In the end, Murry was an even worse disaster as the band’s first manager. A frustrated songwriter himself, he was eventually fired for meddling in their music once too often at which point he sold their peerless song catalogue against their express wishes, a decision that has so far cost them $100m-plus in royalties. Amazingly enough, his portrayal here feels a touch soft-pedalled there are some very lurid stories we seem to be skipping over rather tactfully though I expect it still boils your blood: a particularly nasty childhood beating apparently left Brian deaf in one ear (in one version of the story, Murry hit him with an iron); there was also a mid-’90s court case where it transpired that he had forged his eldest son’s signature on the sale documents of his own songs.

The film tries hard to show that their success was a team effort, underlining the harmonies and fraternal bond between Brian Wilson and his cousin Mike Love and brothers Dennis, Carl and Dennis. (At one point, Love argues that Brian’s mental health problems might have been alleviated had people recognized the fact that there was at least one other genius in the band: Mike Love.) But this is unquestionably a one-man show. Because of his fragile state of mind (he began suffering from auditory hallucinations and was later diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder), as well as the pioneering audacity of his songwriting and arrangements in the 1960s, Brian Wilson has sometimes been cast as an idiot savant. The documentary swiftly disabuses us of that notion. By all accounts he was not only talented but also driven and competitive; “It wasn’t that great a record,” he sniffs of the Beatles’ I Want to Hold Your Hand. He could be a cruel taskmaster too: thrilling footage shows him bossing around LA’s most revered session musicians while barely out of his teens, just as he once bullied his unwilling younger siblings to work on their harmony vocals.

But even his drive couldn’t handle the workload. Never keen on playing live, he suffered his first breakdown on tour in 1964 already in charge of writing, arranging and producing almost everything for the Beach Boys, he had also helmed nine albums in less than three years. Freed from touring duties, he made some of the best music not only of his life but arguably anyone’s; lushly beautiful time-warps permeated by sadness (even Good Vibrations’ euphoria carries an odd yearning). But then drugs did their thing; so did intra-band acrimony; so did America’s cool response to 1966’s Pet Sounds, which sent him spinning further into decline mental ill-health led him to abandon the follow-up, Smile, midway through recording, and from there the Beach Boys’ career looked as good as over.

The group were laughed out of fashion by the counterculture, though their dealings with hippiedom only made things worse. By 1968, Dennis was hanging out with Charles Manson and introducing him to music-biz contacts including his pal Terry Melcher who just happened to be the former occupant of the house at 10050 Cielo Drive when it was visited by members of Manson’s “Family” on the night of the Tate-LaBianca murders. “It wasn’t Dennis’s fault,” Jardine says plaintively; Dennis thought it was. The group soldiered on, Carl and Dennis taking up songwriting duties and sometimes persuading Brian to leave his bedroom and join them in the studio. They made some great records 1970’s Sunflower, 1971’s Surf’s Up which sank without trace. Then came Endless Summer and Brian’s recovery.

The documentary ignores what happened next, which is another series of flop albums (this time around critically), Brian’s second steep decline into mental illness and Dennis’ fatal downward spiral in 1983. Nor does it mention Eugene Landy, the psychiatrist who controlled every aspect of his life and art while probably saving his life too. After making himself Brian’s business manager, executive producer, songwriting partner and financial adviser and getting him to change his will so he was its main beneficiary Landy was eventually prohibited from contacting him by a court order.

Or the succession of lawsuits between band members that consumed the 1990s; or Brian’s return as a solo artiste in the noughties, initially greeted with joy but subsequently accompanied by accusations of exploitation.

Perhaps the last 48 years are left out for reasons of space: the film would need to be twice as long to include them, and the second half would resemble nothing so much as an especially tawdry soap opera. But more likely it’s because they represent a happy ending being appended to a story that doesn’t really have one. That is what happens here: the documentary ends exactly where it began, at least geographically speaking on the beach where they shot their debut album cover. They sit there, apparently shooting the breeze even though Mike Love has just told us that relations between most of them remain strained after a critically acclaimed but notoriously fractious reunion tour in 2012 ended in recriminations not quite the band they seem.

Watch The Beach Boys For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)