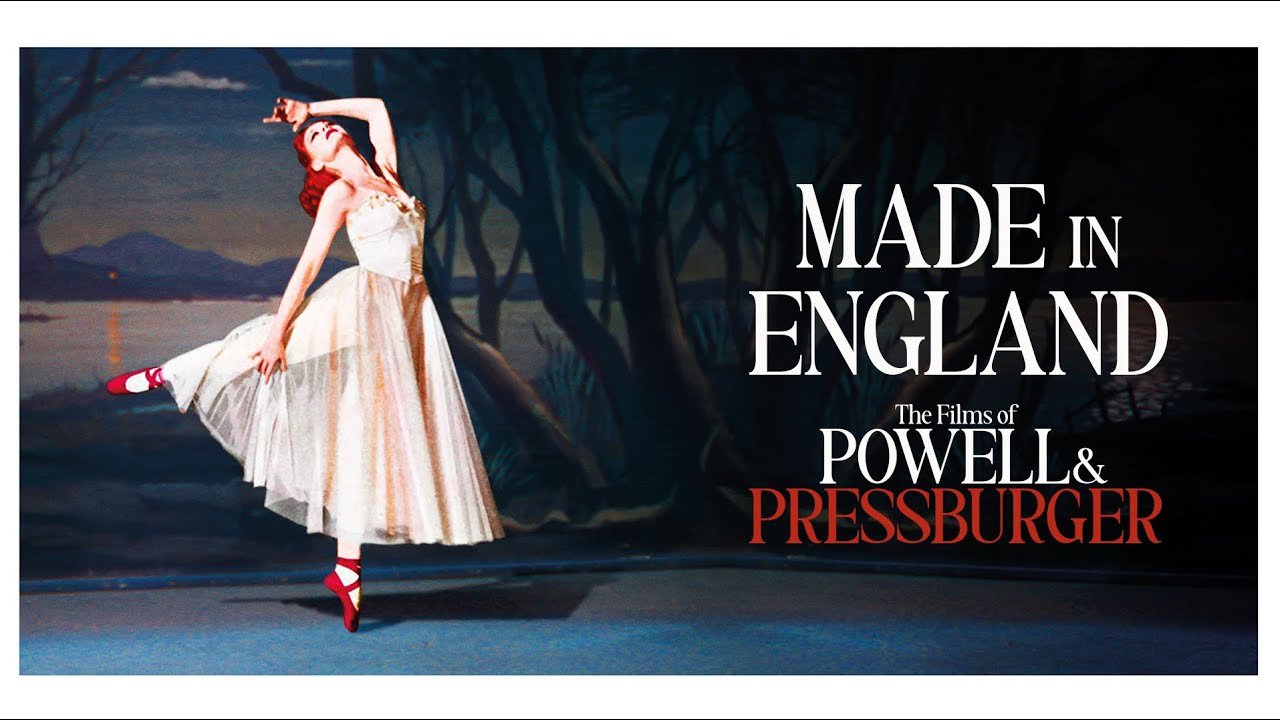

Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger Review

When you grow up watching Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, it’s hard not to believe in a benevolent God. The same could be said for “A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies,” the essential ’90s cinephile primer — or both, as was the case with this writer. In other words, “Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger,” arrives as an unmitigated treat.

David Hinton’s documentary is just that: a straightforwardly constructed trawl through the dizzy highs and sporadic lows of the most — let me stress this again — iridescently fabulous filmography in British cinema. It would have been enough if Hinton had simply assembled a feature-length clip reel; that he got Martin Scorsese to narrate, brought him back after “Personal Journey” to do another tour of duty with the same blend of scholarly authority and avuncular enthusiasm (Martin loves movies), turns an already attractive proposition into more than just another doodle in a movie lover’s notebook. This is a love letter, both from one filmmaker to another and from one generation of film buffs to the next, shortening the distance between youthful discovery and senior nostalgia.

To say that “Made in England” arrives at an opportune moment is something of an understatement: Last fall saw a British Film Institute retrospective followed by nationwide re-releases of “The Red Shoes” (1948) and “Peeping Tom” (1960); six titles made Sight & Sound magazine’s 2022 edition of their Greatest Films poll; even so-called lesser works such as “Gone to Earth” (1950) are now mentioned in hushed tones usually reserved for holy texts. If anything, Hinton has probably made his film too soon: I can’t help but think what it might have done for British cinema had this kind of stateside endorsement come 20 or 30 years ago. But then again, nobody was thinking about Powell and Pressburger 20 or 30 years ago — at least not like this.

Scorsese says that it was his generation of American filmmakers and cineastes who began to rehabilitate the duo’s reputation after they fell out of favor with the British industry in the ’60s — which is another way of saying that nobody thought much of them for a while. But by the time Scorsese came across “The Thief of Bagdad” (1940), what had been lost was already being regained: The film was co-directed by Powell but not Pressburger (though one look at its extravagant visual imagination should be enough to clinch it) and seen on TV by a young Scorsese, who didn’t know any better than to love something he couldn’t properly see. He loved them so much, in fact, that when he grew up he tracked down Powell and made friends with him; they even worked together once or twice.

Those personal connections — Powell eventually married Thelma Schoonmaker, Scorsese’s longtime editor, credited here as an executive producer — naturally color the American director’s narration, though never at the expense of insight or perspective. Powell and Pressburger speak for themselves through well-chosen archival interview footage; their films speak for themselves through a generous amount of clips. The result runs long but never dull, given how many movies there are to get through: If you had to trim anything, it would probably be the introduction, which mostly recaps itself later on.

As his narration before the movie-by-movie analysis starts, Scorsese fills in some biographical information: Powell’s start in the film world as a gofer for Rex Ingram at Nice’s Victorine Studios; making “quota quickies” for American producer Jerry Jackson; and Pressburger’s flight from Nazi Germany to Britain, where the Jewish Hungarian had been a screenwriter at Berlin’s UFA Studio. The duo were brought together by British-Hungarian producer Alexander Korda, working on an interim basis as directors-for-hire on 1939 thriller “The Spy in Black” that became a hit; taut anti-Nazi war drama “49th Parallel,” which won Pressburger an Oscar for writing and made their name as a team; they split credits between directing and writing until they formed their own production company, The Archers, in 1943.

Then came their golden age, encompassing such films as romantic anti-war epic “The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp,” said to have rubbed Winston Churchill up the wrong way (“Not a very good film critic,” says Pressburger dryly of the former Prime Minister); heart-clutching afterlife fantasy “A Matter of Life and Death”; sensualist convent psychodrama “Black Narcissus”; and luminous fairytale-riffing ballet tragedy “The Red Shoes.” These coruscating landmarks are spoken by Scorsese with still-rapt awe — occasionally noting the influence he has taken from their editing, music or colour work on his own films (the red light flooding Mean Streets is straight out of Powell and Pressburger, though Powell himself thought it overkill).

But he gives equal attention to more modest monochrome genre offerings that filled out their filmography: wistful romantic comedy I Know Where I’m Going!, bristling wartime noir The Small Back Room — even lesser-loved works receive detailed passages here to illustrate the full extent of his devotion. Of these, a substantial chunk is given over to 1950 neo-romantic rural folk odyssey Gone to Earth — an unhappy collaboration with American super-producer David O Selznick, who reshot and recut it extensively for the US market — which will send many viewers running for a copy on the strength of Scorsese’s besotted analysis and some ravishing, mist-laced scene selections.

Later flops like Oh Rosalinda! and Ill Met By Moonlight are harder for even Scorsese to sell, but put in context of a career buffeted by industry trends; Peeping Tom is given the reverent reappraisal its reclaimed-classic status merits. “When did the British ever appreciate their greatest men?” says a tongue-in-cheek Powell, alongside a cringing Pressburger, in a droll 1980s interview clip from around the time they received a BAFTA Fellowship; that award marked their gradual re-embrace by a previously sniffy local industry toward unimpeachable master status that this bright, doting documentary underlines. With amiable nerdy insistence, Scorsese reminds us he was on that page all along.

Watch Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)