McVeigh Review

“One of the many vague extremists that surround Mike Ott’s tense drama McVeigh says ‘We have to do something,’” which recounts Timothy McVeigh’s (an Iraq war veteran) decision to blow up the Oklahoma-based Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building on 19 April 1995, killing 168 people and injuring another 680; he was executed on the same day as his white supremacist accomplice, Richard Snell for whom he had great affection – though why this man should still need any airtime almost 23 years after he died is beyond me or anyone else coloured in this room. But Ott’s film provides a rare examination into how working-class white Americans become radicalized, something that became evident when rioters stormed Washington DC on January 6th this year.

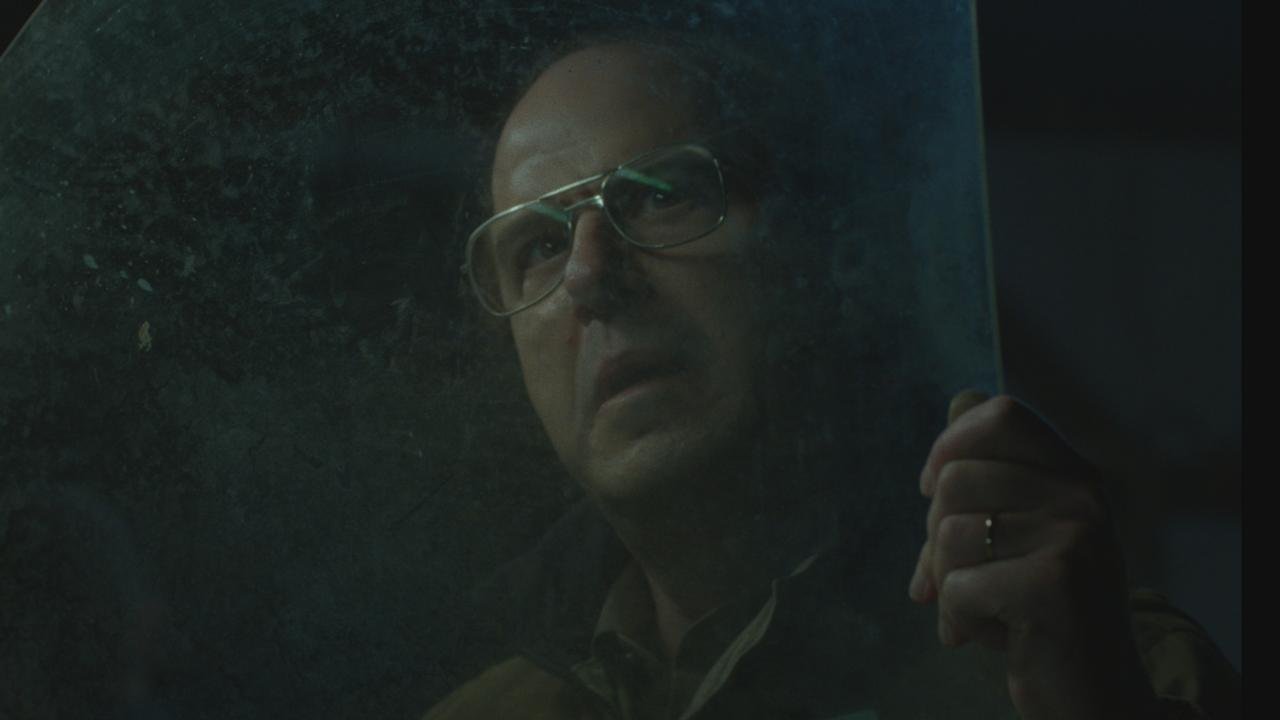

Ott keeps us at arm’s length from his subject throughout, a directorial choice made clear from the start: unless we’re following Britain’s Alfie Allen as McVeigh (who does a good job with what little he has), we’re watching him — often in his car — like an animal. Master shots are used, or medium close-ups which slowly zoom in but never get too close; much is left unseen such as in the opening scenes where he gets pulled over for speeding: while the traffic cop writes out a ticket behind him, McVeigh looks anxious and Ott takes us towards what must be causing it: the glove compartment.

It doesn’t matter what’s actually inside it because McVeigh is against any kind of authority already — especially since they burned down his church during their violent siege of Waco Texas in ’93 led by David Koresh — so instead he keeps his head down working stalls at guns-and-ammo shows where he sells bumper stickers for $2 each (“The day government outlaws guns is day I’ll become an outlaw” reads one). This brings him into contact with Frédéric (Anthony Carrigan), who knows about McVeigh’s relationship with Snell (Tracy Letts) but leaves him hanging for now.

Terry (Brett Gelman) seems to be McVeigh’s only friend, a nerdy racist redneck with a Filipino wife who eggs him on against the government until he buys so much fertilizer and nitromethane barrels that even Terry starts to get worried; Frédéric is there for him though, when no one else will be. “We need some real f*ckin’ soldiers who ain’t scared” he says from his conveniently safe distance.

These deliberately austere true stories are their own genre — for reference see Alexandre Moors’ 2013 Sundance sleeper Blue Caprice (about the 2002 DC beltway sniper attacks) or more pertinently Gus Van Sant’s Palme d’Or-winning Elephant (2003), inspired by Columbine — and might also owe something to Spanish director Jaime Rosales’ virtually wordless Bullet in the Head (2008), in which Basque terrorists carry out hit on two policemen; as in that film, dialogue is often replaced by ambient sound cranked up to unbearable levels.

No doubt questions of taste will circle around this film, especially with a British person in the lead role, but McVeigh does nonetheless show the pipeline — if that’s what it is, maybe it’s a conveyor belt — that turns fragile egos into so-called “lone wolf” terrorists. Maybe too on-the-nose for a commercial audience given the current state of American politics, Ott’s movie has an abrupt and confusing coda that is honestly beyond comprehension: It’s information overload that tries to match the scrambled madness of right and wrong in McVeigh’s head (sorry, but there are no brownie points for throwing in a near-subliminal nod to the CIA’s controversial MK Ultra program at this late stage).

That said, I do think McVeigh adds something new to discussions about radicalization: According to him it isn’t religion or race or mental illness but rather filling up an empty vessel. The devil will always find work for idle hands to do — as Timothy McVeigh demonstrated when he shocked and horrified everyone.

Watch McVeigh For Free On Gomovies.

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.webp?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=1024&resize=1024,1024&ssl=1)